Secret Goldman Sachs tapes show regulators still respect bankers too much - The Washington Post

The problem with Wall Street's cops is that, before the crisis, they didn't actually fall asleep on the job.

Regulators

knew the big banks were taking big risks, and had the power to do

something about it. But they didn't. It's worse than outright neglect,

since it's not as obvious how to fix it. And now, thanks to 46 hours of secret audio tapes

from inside the New York Federal Reserve, we can hear that they're

still having trouble fixing it. The problem isn't that regulators don't

have the tools they need. It's that they won't use the tools they have,

because they respect the bankers too much.

...

This is where you need to go to This American Life, who, in conjunction with Jake Bernstein

of ProPublica, put together the highlights of Segarra's 46 hours of

audio recordings. You have to hear how obsequious the supervisors sound

when they talk to Goldman's executives, almost apologetic for not-quite

doing their jobs. The best example of this came during a deal between

Goldman and the Spanish banking behemoth Banco Santander in 2012. "We're

looking at a transaction that's legal but shady," Segarra's boss Mike

Silva said, and "I want to put a big shot across their bow on that."

Specifically, Goldman was making it look like it was taking assets from

Santander without really doing so — for a fee, of course — all so

Santader could avoid having to raise more capital. This was regulatory

arbitrage of the worst kind: It was potentially destabilizing. But the

term sheet said the deal wouldn't go ahead unless the New York Fed

explicitly signed off on it. Until, that is, Goldman just went ahead

without it.

...

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Americans Continue to Say a Third Political Party Is Needed

Americans Continue to Say a Third Political Party Is Needed - Gallup

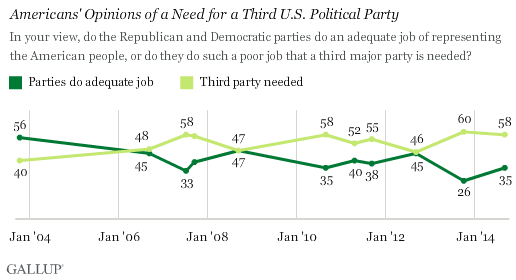

A majority of U.S. adults, 58%, say a third U.S. political party is

needed because the Republican and Democratic parties "do such a poor

job" representing the American people. These views are little changed

from last year's high. Since 2007, a majority has typically called for a third party.

The results are based on Gallup's Sept. 4-7 Governance poll. The

The results are based on Gallup's Sept. 4-7 Governance poll. The

first time the question was asked in 2003, a majority of Americans

believed the two major parties were adequately representing the U.S.

public, which is the only time this has been the case. Since 2007, a

majority has said a third party is needed, with two exceptions occurring

in the fall of the 2008 and 2012 presidential election years.

The historical 60% high favoring a third party came in a poll

conducted during the partial federal government shutdown last October.

At that time, 26% of Americans said the parties were doing an adequate

job. That figure is up to 35% now, but with little change in the

percentage calling for a third party.

Americans' current desire for a third party is consistent with their generally negative views of both the Republican and Democratic parties,

with only about four in 10 viewing each positively. Americans' views

toward the two major parties have been tepid for much of the last

decade. However, even when the party's images were more positive in the

past, including majority favorability for the Democrats throughout 2007

and favorability for the GOP approaching 50% in 2011, Americans' still

saw the need for a third party.

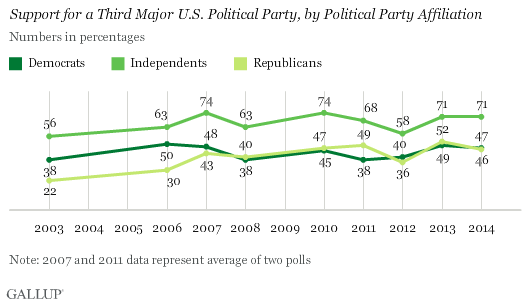

Independents Maintain Solid Preference for Third Party

Political independents, as might be expected given a lack of

allegiance to either major party, have shown a far greater preference

for a third political party than those who identify as Republicans or

Democrats. Currently, 71% of independents say a third party is needed,

on the upper end of the trend line. That compares with 47% of Democrats

and 46% of Republicans who say the same.

For most of the past 11 years, Republicans and Democrats were about

For most of the past 11 years, Republicans and Democrats were about

equally as likely to favor a third party. From 2003 to 2006 -- when

Republicans had control of the presidency and both houses of Congress --

Democrats were more likely than Republicans to see the need for a third

party. And in 2011, after the rise of the Tea Party movement,

Republicans were a bit more inclined than Democrats to see a third party

as necessary.

Implications

Although Americans express a desire for a viable alternative to the

Democratic and Republican parties, third political parties have had

little success in American politics. The U.S. political system makes it

difficult for third parties to hold elected office given the Electoral

College system of electing presidents and election of members of

Congress from individual states and districts based on the candidate

getting the most votes. Such a system generally favors two parties -- a

center-right and a center-left party -- that have the ability to

assemble a winning plurality or majority in districts and states across

the country. Also, some states have restrictive laws on ballot access

that make it difficult for third-party candidates to appear on the

ballot.

Third parties have had success in other countries when they had

strong support in a particular region, or if members of the legislature

were allocated proportionately to the nationwide vote each party

received. This allowed third parties to hold seats with national vote

shares usually well less than 30%.

Given the U.S. political system, those whose ideology puts them to

the left of the Democratic Party or the right of the Republican Party

are better served trying to work within a major political party than

establishing their own party. Supporters of the Tea Party movement

generally took this approach, with some success, by trying to get their

preferred candidates nominated as Republicans in the last few election

cycles. But as with most U.S. third parties historically, the Tea

Party's influence appears to be waning as the movement did not play a

pivotal role in the 2012 Republican presidential nomination and was less

successful in defeating more moderate Republican candidates in the 2014

congressional primaries than in 2010.

Though the desire for a third party exists, it is unclear how many

Americans would actually support a third party if it came to be.

Americans' preference for a third party may reflect their frustration

with the way the Republican and Democratic parties are performing, as

well as the idea that the system ought to be open to new parties,

regardless of whether this is viable in practice.

A majority of U.S. adults, 58%, say a third U.S. political party is

needed because the Republican and Democratic parties "do such a poor

job" representing the American people. These views are little changed

from last year's high. Since 2007, a majority has typically called for a third party.

first time the question was asked in 2003, a majority of Americans

believed the two major parties were adequately representing the U.S.

public, which is the only time this has been the case. Since 2007, a

majority has said a third party is needed, with two exceptions occurring

in the fall of the 2008 and 2012 presidential election years.

The historical 60% high favoring a third party came in a poll

conducted during the partial federal government shutdown last October.

At that time, 26% of Americans said the parties were doing an adequate

job. That figure is up to 35% now, but with little change in the

percentage calling for a third party.

Americans' current desire for a third party is consistent with their generally negative views of both the Republican and Democratic parties,

with only about four in 10 viewing each positively. Americans' views

toward the two major parties have been tepid for much of the last

decade. However, even when the party's images were more positive in the

past, including majority favorability for the Democrats throughout 2007

and favorability for the GOP approaching 50% in 2011, Americans' still

saw the need for a third party.

Independents Maintain Solid Preference for Third Party

Political independents, as might be expected given a lack of

allegiance to either major party, have shown a far greater preference

for a third political party than those who identify as Republicans or

Democrats. Currently, 71% of independents say a third party is needed,

on the upper end of the trend line. That compares with 47% of Democrats

and 46% of Republicans who say the same.

equally as likely to favor a third party. From 2003 to 2006 -- when

Republicans had control of the presidency and both houses of Congress --

Democrats were more likely than Republicans to see the need for a third

party. And in 2011, after the rise of the Tea Party movement,

Republicans were a bit more inclined than Democrats to see a third party

as necessary.

Implications

Although Americans express a desire for a viable alternative to the

Democratic and Republican parties, third political parties have had

little success in American politics. The U.S. political system makes it

difficult for third parties to hold elected office given the Electoral

College system of electing presidents and election of members of

Congress from individual states and districts based on the candidate

getting the most votes. Such a system generally favors two parties -- a

center-right and a center-left party -- that have the ability to

assemble a winning plurality or majority in districts and states across

the country. Also, some states have restrictive laws on ballot access

that make it difficult for third-party candidates to appear on the

ballot.

Third parties have had success in other countries when they had

strong support in a particular region, or if members of the legislature

were allocated proportionately to the nationwide vote each party

received. This allowed third parties to hold seats with national vote

shares usually well less than 30%.

Given the U.S. political system, those whose ideology puts them to

the left of the Democratic Party or the right of the Republican Party

are better served trying to work within a major political party than

establishing their own party. Supporters of the Tea Party movement

generally took this approach, with some success, by trying to get their

preferred candidates nominated as Republicans in the last few election

cycles. But as with most U.S. third parties historically, the Tea

Party's influence appears to be waning as the movement did not play a

pivotal role in the 2012 Republican presidential nomination and was less

successful in defeating more moderate Republican candidates in the 2014

congressional primaries than in 2010.

Though the desire for a third party exists, it is unclear how many

Americans would actually support a third party if it came to be.

Americans' preference for a third party may reflect their frustration

with the way the Republican and Democratic parties are performing, as

well as the idea that the system ought to be open to new parties,

regardless of whether this is viable in practice.

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

The Recovery That Left Out Almost Everybody

The Recovery That Left Out Almost Everybody - WSJ -Yahoo Finance

According to a Pew Research

Center report released this month, only 21% rate current conditions as

excellent or good, versus 79% fair or poor. Only 33% say that jobs are

readily available in their communities; when asked about good jobs, that

figure falls to 26%. Only 22% believe the economy will be better a year

from now; 22% think it will be worse, while fully 54% think it will be

the same.

According to a Pew Research

Center report released this month, only 21% rate current conditions as

excellent or good, versus 79% fair or poor. Only 33% say that jobs are

readily available in their communities; when asked about good jobs, that

figure falls to 26%. Only 22% believe the economy will be better a year

from now; 22% think it will be worse, while fully 54% think it will be

the same.

More than five years after the

official end of the recession, the Public Religion Research Institute

finds, only 21% of Americans believe the recession has ended.

official end of the recession, the Public Religion Research Institute

finds, only 21% of Americans believe the recession has ended.

Two recent reports help explain

the disconnect between the official jobs numbers and the economic

experience of most Americans. Every fall, the U.S. Commerce Department

issues a detailed analysis of trends in income, poverty and health

insurance. Although economists have some technical quibbles with the

Commerce data, the broad trends are unmistakable.

the disconnect between the official jobs numbers and the economic

experience of most Americans. Every fall, the U.S. Commerce Department

issues a detailed analysis of trends in income, poverty and health

insurance. Although economists have some technical quibbles with the

Commerce data, the broad trends are unmistakable.

This year's report found that

median household income was $51,939 in 2013, 8% lower than in 2007, the

last year before the recession. Households in the middle of the income

distribution earned about $4,500 less last year than they had six years

earlier. No wonder 56% of Americans told the Pew Research Center that

their incomes were falling behind the cost of living.

median household income was $51,939 in 2013, 8% lower than in 2007, the

last year before the recession. Households in the middle of the income

distribution earned about $4,500 less last year than they had six years

earlier. No wonder 56% of Americans told the Pew Research Center that

their incomes were falling behind the cost of living.

The Federal Reserve's triennial

Survey of Consumer Finances confirms these findings. Between 2010 and

2013, the Fed reports, median family income fell by 5%, even though

average family income rose by 4%. This is, note the authors, "consistent

with increasing income concentration during this period." Only families

in the top 10%, with annual incomes averaging nearly $400,000, saw

gains during these three years. Families headed by college graduates

eked out a gain of 1%, while those with a high-school diploma or less

saw declines of about 7%. Those in the middle—with some postsecondary

education—did the worst: From 2010 to 2013, their annual incomes

declined to less than $41,000 from $46,000—an 11% plunge. Families

headed by workers under age 35 have done especially badly—even when the

heads of those young families have college degrees. The economic

struggles of the millennials are more than anecdotal.

Survey of Consumer Finances confirms these findings. Between 2010 and

2013, the Fed reports, median family income fell by 5%, even though

average family income rose by 4%. This is, note the authors, "consistent

with increasing income concentration during this period." Only families

in the top 10%, with annual incomes averaging nearly $400,000, saw

gains during these three years. Families headed by college graduates

eked out a gain of 1%, while those with a high-school diploma or less

saw declines of about 7%. Those in the middle—with some postsecondary

education—did the worst: From 2010 to 2013, their annual incomes

declined to less than $41,000 from $46,000—an 11% plunge. Families

headed by workers under age 35 have done especially badly—even when the

heads of those young families have college degrees. The economic

struggles of the millennials are more than anecdotal.

What's going on? The Census

report offers a clue. The median earnings for Americans working

full-time year round haven't changed much since 2007. But more than five

years into the recovery, there are fewer such workers than before the

recession. In 2007, 108.6 million Americans were working full time,

year-round; in 2013 only 105.9 million were doing so. Although jobs are

being created, too many of them are part-time to maintain growth in

household incomes.

report offers a clue. The median earnings for Americans working

full-time year round haven't changed much since 2007. But more than five

years into the recovery, there are fewer such workers than before the

recession. In 2007, 108.6 million Americans were working full time,

year-round; in 2013 only 105.9 million were doing so. Although jobs are

being created, too many of them are part-time to maintain growth in

household incomes.

This is not by choice. About

the same number of Americans were employed last month as in December

2007. But during that period, according to the Bureau of Labor

Statistics, the number of Americans working part time who wanted a

full-time job jumped to 7.2 million from 4.6 million. Not only are

hourly wages stagnating; America's families want more hours of work than

the economy is providing.

the same number of Americans were employed last month as in December

2007. But during that period, according to the Bureau of Labor

Statistics, the number of Americans working part time who wanted a

full-time job jumped to 7.2 million from 4.6 million. Not only are

hourly wages stagnating; America's families want more hours of work than

the economy is providing.

Although the Great Recession

was the most severe since World War II, in many ways it underscored

trends that have been under way for decades. Adjusted for inflation,

median earnings of men working full time, year-round are no higher than

they were in 1980. Median household income is almost $5,000 lower than

it was in 1999, and no higher than it was it 1989.

was the most severe since World War II, in many ways it underscored

trends that have been under way for decades. Adjusted for inflation,

median earnings of men working full time, year-round are no higher than

they were in 1980. Median household income is almost $5,000 lower than

it was in 1999, and no higher than it was it 1989.

The modest income increases of

the past two generations have occurred because women have surged into

the paid workforce—and because their real wages have grown at a compound

annual rate of 0.8%. But both these trends peaked in 2000. Not

surprisingly, the years after the 2001 recession witnessed the only

postwar recovery in which median incomes failed to regain their previous

peak.

the past two generations have occurred because women have surged into

the paid workforce—and because their real wages have grown at a compound

annual rate of 0.8%. But both these trends peaked in 2000. Not

surprisingly, the years after the 2001 recession witnessed the only

postwar recovery in which median incomes failed to regain their previous

peak.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)